Developing age-friendly communities in urban regeneration projects

There is growing recognition that the housing offer in the UK is out of step with the needs and aspirations of older people. The housing crisis in the UK (and other European countries), is reflected in the limited housing options available for both younger and older age groups.

Researchers, policy-makers and service- providers need to consider the changing needs of older people both now and in the future, together with their families and the communities in which they live.

Urban regeneration

In response to the urgent demand for housing for different generations, local authorities in urban areas are engaged in ambitious redevelopment projects. For example, in 2018, Manchester announced the largest and most ambitious residential-led development in its history, with plans for up to 15,000 homes to be built over a 15-20 year period.

The project, called the Northern Gateway, represents a major contribution to the City’s strategy for residential growth and involves a collaboration with private developers, the Hong Kong-based Far East Consortium International Limited.

Aerial view of the Northern Gateway boundary. Source: Northern Gateway

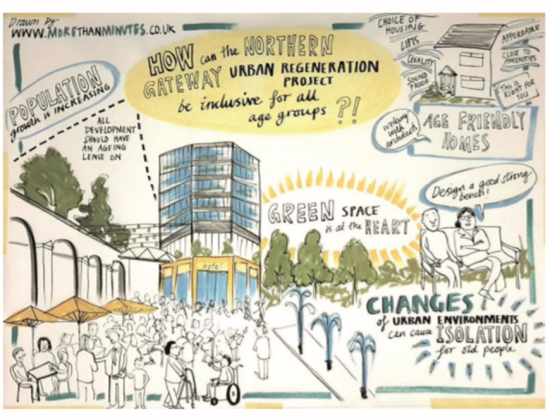

Manchester City Council hold a unique ambition, to create the Northern Gateway as an age-friendly urban regeneration project.

Changing demographics

Given the shifting age demographics reshaping society, ageing needs to be central to debates about urban redevelopment (opens new window) and how we design our towns, cities and communities. It is vital that urban regeneration delivers suitable and accessible housing, in communities that enable us to age well (opens new window).

Increased awareness and consideration of this issue, and greater efforts to address ageing in urban regeneration projects from local authorities, private developers and stakeholders is essential to the needs of the growing ageing communities in cities.

The number of older people in Manchester is set to rise substantially. Estimates suggest that by the year 2036, 14% of the total population living in Greater Manchester will be aged 75 and over. This is an increase of 75% (2011), from 221,000 to 387,0004. Compared to the national average, a greater proportion of older people in Manchester are income deprived. In view of these trends, targeting urban regeneration strategies at different groups within the older population is essential.

In order for the Northern Gateway to become an age-friendly regeneration site, it will be vital to consider the contrasting needs of a) different ethnic groups, b) those with particular physical/ mental health needs, and c) those living in areas marked by economic, health and social inequalities of various kinds.

Collyhurst, Manchester

Collyhurst, one of the neighbourhoods included in the Northern Gateway redevelopment consists predominantly of socially rented properties – 1070 in total – with 77% of older people living in this type of accommodation.

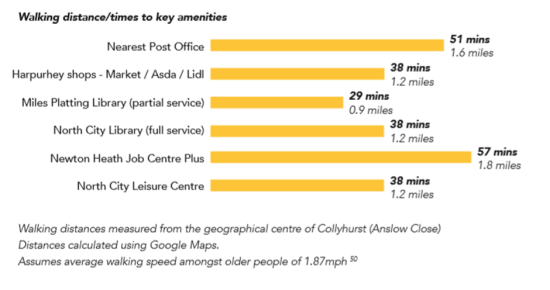

Waves of demolition and population decline have resulted in the loss of shops and social infrastructure. Collyhurst has no significant retail outlets and limited public services, with residents having to travel to nearby Harpurhey or Cheetham to access key amenities such as libraries, leisure centres or to buy groceries or collect a prescription.

Walking distances/times to key amenities: Source: Mark Hammond, Developing age-friendly communities in the Northern Gateway urban regeneration project.

The proposal is for a mixture of housing types and tenures, offering both social and affordable homes. Collyhurst is a site which has been reshaped by the decline of local industries, demolition of housing, and loss of population.

Building an age-friendly neighbourhood

In order to become an age-friendly neighbourhood, the Northern Gateway should prioritise the needs of existing residents to be able to access services and amenities in the new Collyhurst. Residents stressed that the newly regenerated area should include more social spaces such as a community centre, ‘a place for entertainment’, and somewhere where older and younger people could gather, like a social club.

The proposed vision for Collyhurst set out in the Northern Gateway proposals Source: Northern Gateway / Adriette Myburgh

Innovative new approaches will be required in order to ensure that new housing is attractive, accessible, adaptable, and within financial reach of those who wish to move, and that programmes are in place to support residents who want to remain in their current homes and neighbourhoods.

Developers should be encouraged to explore and address the needs and aspirations of older people across tenures, recognising emerging trends in the housing movements of older people. These include older people entering or remaining in the private sector in later life, the increased number of older people experiencing divorce or separation in later life, and the increased desirability of urban neighbourhoods for the emerging cohort of older people.

Placing older people’s experiences at the heart of the agenda is essential, in order to give older people a voice so they can be involved in making decisions about future homes and neighbourhoods in the city.

Recommendations

Future regeneration should offer mixed, affordable and age-appropriate housing. Building new, (opens new window) accessible homes (opens new window) will be of benefit (opens new window)to all generations. Ensuring they are inclusively designed homes (opens new window) will help people to remain independent, safe and socially connected in later life.

- Urban regeneration should ensure that people can remain actively involved in their neighbourhood as they grow older, staying connected to those who matter to them. This means including a wide range of spaces like libraries and community centres so that people can interact across all age groups.

- Developers should address the needs and aspirations of older people across different tenures (opens new window) (including social housing, private rental and owner-occupier), recognising emerging trends among older age groups. These include: entering or remaining in the private sector, the increased number of people experiencing divorce or separation, and the increased interest in city-centre living.

- Urban regeneration plans should try to avoid the spatial segregation of different groups within the community, particularly the separation of residents by age group, tenure, and property size. For many people, an age-friendly community is one that they share with people at different life stages, not a type of specialist housing.

- Regeneration should aim to share the benefits it brings between long-term residents and newcomers. This can be done by supporting existing community spaces and keeping the place’s identity at the heart of new developments.

Visual minutes of the ‘Developing Age-Friendly Cities’ workshop, June 2019 Source: University of Manchester / MoreThanMinutes.co.uk

This research was carried out with Mark Hammond, Niamh Kavanagh, Chris Phillipson and Sophie Yarker and was funded by the Centre for Ageing Better and Age Friendly Manchester. For more information, contact camilla.lewis@newcastle.ac.uk.

If you found this blog of interest, check out Pozzoni Architecture’s Nigel Saunders’ related guest blog, A design for later life – senior living and intergenerational communities

Comments

Add your comment